Dante is a witness, who sees and feels on behalf of the reader

Karl Ove Knausgaard, “At the Bottom of the Universe,” 152

Author: Darin

-

Witness

-

Longing

I find the world unknowable and therefore fascinating, unfamiliar and therefore irresistible. I long for that space where life seems uncertain, where I have to revise or reject the comfortable assumptions and convictions that have structured my life.

Urban #240311.1. I used to frequent a local coffee shop where I often saw a particular woman. Whenever she saw me, she would move to the table next to mine and start writing on whatever piece of paper she had available. After a few minutes, she would hand me the piece of paper covered in rapid scrawlings and signed AST, smile, and then sit silently. I don’t recall her ever speaking to me. I don’t see her any longer — the coffee shop has closed. I miss our encounters. I learned a lot from watching her and trying to understand her world, which was very different from mine. Now and then, when I’m feeling smug, I pull out those sheets of paper and look back over them.

Urban #240311.2. A few years back, an incarcerated man sent me a couple letters outlining his critique of society. Pages filled with carefully hand-written words, each letter almost typewriter perfect. Diagrams drawn with draftsman like precision. In the upper left corner, in place of a staple, an orange thread pierced the pages and stitched them together. Another encounter with a world that is very different from mine. Those letters are in the drawer with the pages from AST.

Urban #240311.3. These encounters with the absurdity of life give me energy. Some unanswered and probably unanswerable longing for the unknown drives me. That longing is the wellspring of all my creativity, which might turn out to be ravings of a lunatic, but what higher purpose can there be for creativity.

-

Courage

The dismal fact is that self-respect has nothing to do with the approval of others — who are, after all, deceived easily enough; has nothing to do with reputation, which, as Rhett Butler told Scarlett O’Hara, is something people with courage can do without.

J. Didion, “On Self-Respect” -

On Taking Notes

The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who don’t share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself.

J. Didion, “On Keeping a Notebook” -

Of Bicycles and Cameras

Thumbing through a couple books recently — one a collection of photographs, one a book on improving your photographic skills – made something clear: Photographers commonly feel compelled to draw attention to their cameras and their camera settings, whether or not that information serves any purpose. I remain amused by photographers’ obsession with equipment; it reminds me of the ways cyclists sit around and talk about bicycles.

Landscape #230615. If you end up in a trendy, upscale café on a weekend, chances are you’ve seen and heard the crowds of mostly guys, many of them older, sitting in lycra talking about the morning’s ride. An important part of that conversation revolves around their equipment, sometimes in subtle ways, sometimes not so subtle. One might talk about what gears he used in the sprint or on the climb. Another might talk about the stiffness of his carbon-fiber frame. Another might mention frame geometry. Cycling computers are often topics of conversation. Somebody inevitably brings up a recent review of equipment or an article about some professional’s Tour de France bike. None of this talk improves anybody’s cycling skills or fitness. So from the perspective of getting better, it’s useless. However, a significant part of their enjoyment, it seems, comes not from riding but from sitting around and talking about their bikes.

Photographers seem to share this need to draw attention to their equipment. References to camera, lens, settings recall the cyclists talking about their gear choices for a climb. It doesn’t matter. You made it (or didn’t) to the top of the climb, just as you took the picture (or didn’t). What matters in cycling is: Did you make it to the top of the climb as quickly as you wanted? If so, great. If not, go ride more. In photography, what matters is: Did you get the picture you wanted? If so, great. If not, go take more pictures. And yet, in both the collection of photographs and the book on improving your photographic skills, captions include the location, year, camera body, the lens, the aperture, the shutter speed, and the ISO. None of that should matter, either for the viewer or the student.

At some level I think photographers know that their equipment and settings don’t matter. After drawing attention to their equipment, they rarely even try to explain how it has affected their photographs. Even the author/photographer of the book on improving your photographic skills never refers to the camera and settings. I would expect an “educator” to explain the relevance of such information, were it, in fact, relevant. I would love to see how the camera body mattered, as if it were a choice he or any photographer would make before taking any given photograph. Imagine the photographer who sees an interesting scene, then thinks: Would this be better shot with a Canon 5D mk II or a Fuji X-T2 or a Nikon D810. I would also love to see that photographer in the wild, digging through a massive bag of gear that included different bodies and different sets of lenses and perhaps flashes. No, the camera doesn’t matter. This educator, like most of us, probably grabbed whatever camera he was using that year or on that trip, i.e., the camera he had with him. Nothing more.

To be clear, I think we all find find equipment that for some personal reason we enjoy using. And because we enjoy using that equipment, it might help us realize our creative projects or help us become better photographers (if that’s our goal). Just as the old guys in lycra at the café don’t become better cyclists by talking about their bicycles, we don’t become better photographers by talking about our cameras.

-

The Tyranny of “Style”

Style has become both a fetish and a marketing device. We read or, more likely in today’s podcast- and YouTube-dominated world, hear and see over and over again that we have to discover our style as if it’s some buried treasure or a form of therapeutic self-realization (the alternative formulation, “we have to find our style” doesn’t change the point). The person telling us to find our style usually offers to help us do so, adopting a sort of guru or therapist role, or, equally often, offers to sell us a class to lead us along the path to illumination. All this focus on style seems to be, at best, misguided or, more likely, fraudulent.

Urban #230917 Style is now a commodity that people sell. In marketing pitches, they link photographic success to finding a style. They dream up exercises and techniques, not for taking pictures or making photographs or thinking about what interests you, but for developing your style. They talk about visual consistency. Although they are quick to say style is more than a set of presets, they then reduce style to a set of prescribed actions that enables you to achieve this consistency of look, as if homogeneity were a desideratum. And they promise to help you find your look. Free newsletters are gateway drugs to $150/hour coaching sessions. Free YouTube videos are infomercials for classes and one-on-one sessions. Some talking head teases the viewer with promises of fame and success, usually through tedious and dubious claims about the presenter’s own overnight economic success. Style is always reduced to economic success.

Never do we hear these people promise your photography will be more fulfilling or more rewarding or more enjoyable. They don’t say you’ll be better able to realize your creative vision, or that you’ll make more important photographs (here, David duChemin’s distinction between good and important is relevant here). No. They can only promise financial success. How often they deliver on that promise is an open question.

Imposing a style, i.e., a signature look, has replaced any expression of creativity or individual intentionality, has reduced photography to an iterative almost algorithmic task. Find a particular scene. Photograph it from a particular angle in a particular light. Process in a particular way. To paraphrase and repurpose Lear:

That way madness and homogeneity and boredom lie; let me shun that.

No more of that.To be clear, I think that after doing something over and over again and with intentionality, a person will create a style. Klinkenborg’s comment seems appropriate here: style is the “fusion of your command of [visual] language and your commitment to your own intent.” Importantly, “you don’t need to think about style.”

Countless artists developed a style, but not by focusing on style. See, e.g., Lucas Cranach the Elder or Albrecht Dürer or Hieronymous Bosch or Giuseppe Archimboldo or Pieter Breugel since I’m in a Northern Renaissance mood. They produced lots and lots and lots of drawings, paintings , sketches, and engravings. Their style emerged, as Klinkenborg puts it, through their command of the relevant language and their commitment to their own intent.

No, the style gurus can’t teach style. They can teach rules. But rules are not style, as Mavis Gallant reminds us:

Working to rule, trying to make a barely breathing work of fiction simpler and more lucid and more euphonious merely injects into the desperate author’s voice a tone of suppressed hysteria, the result of what E. M. Forster called “confusing order with orders.”

M. Gallant, “What is Style?” in Paris Notebooks, 259–260Gallant’s comment applies equally to photography, and probably every other creative endeavor.

-

On Painting

No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.

P. Picasso in interview with Simone Téry, March 24, 1945. -

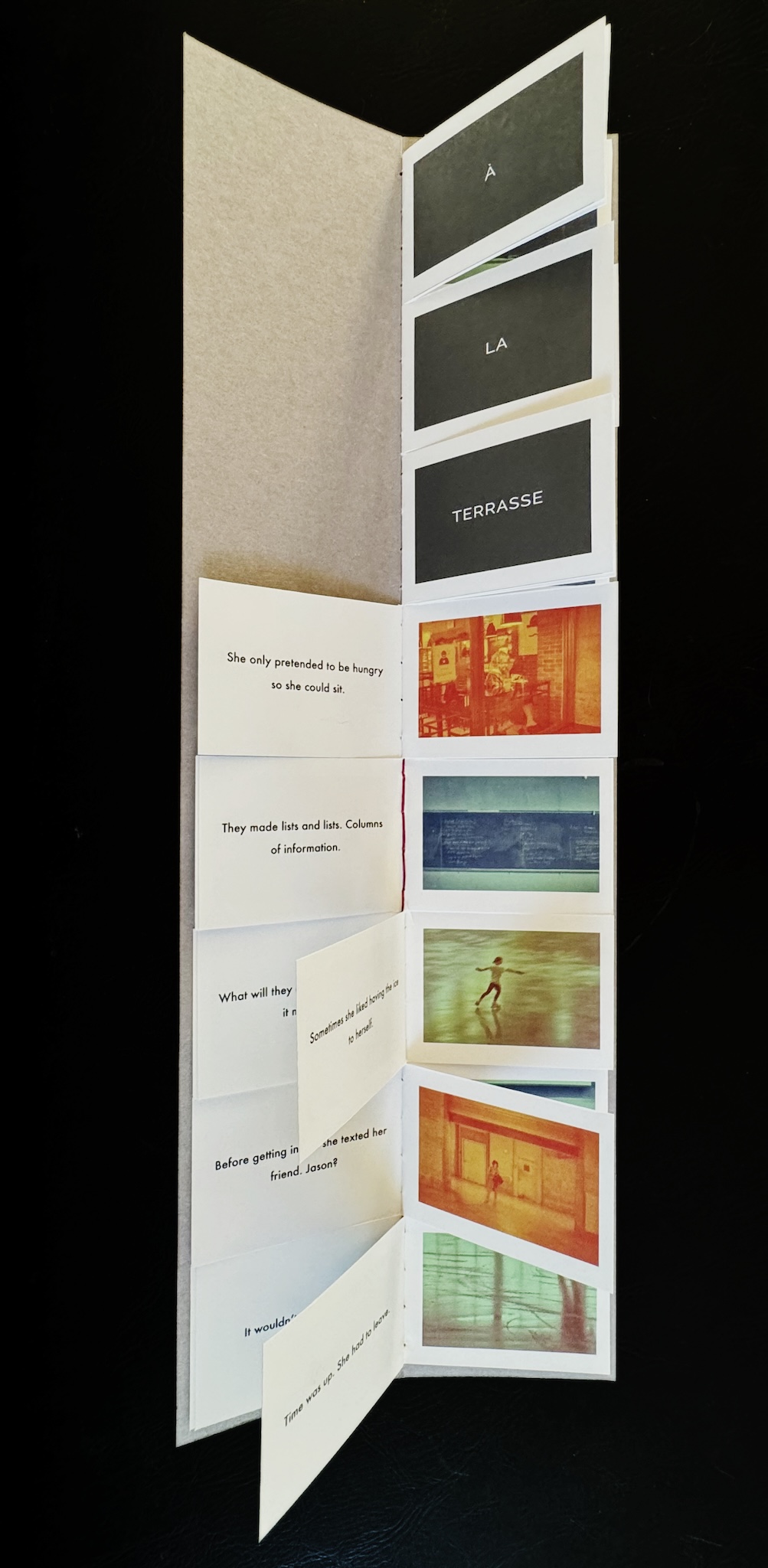

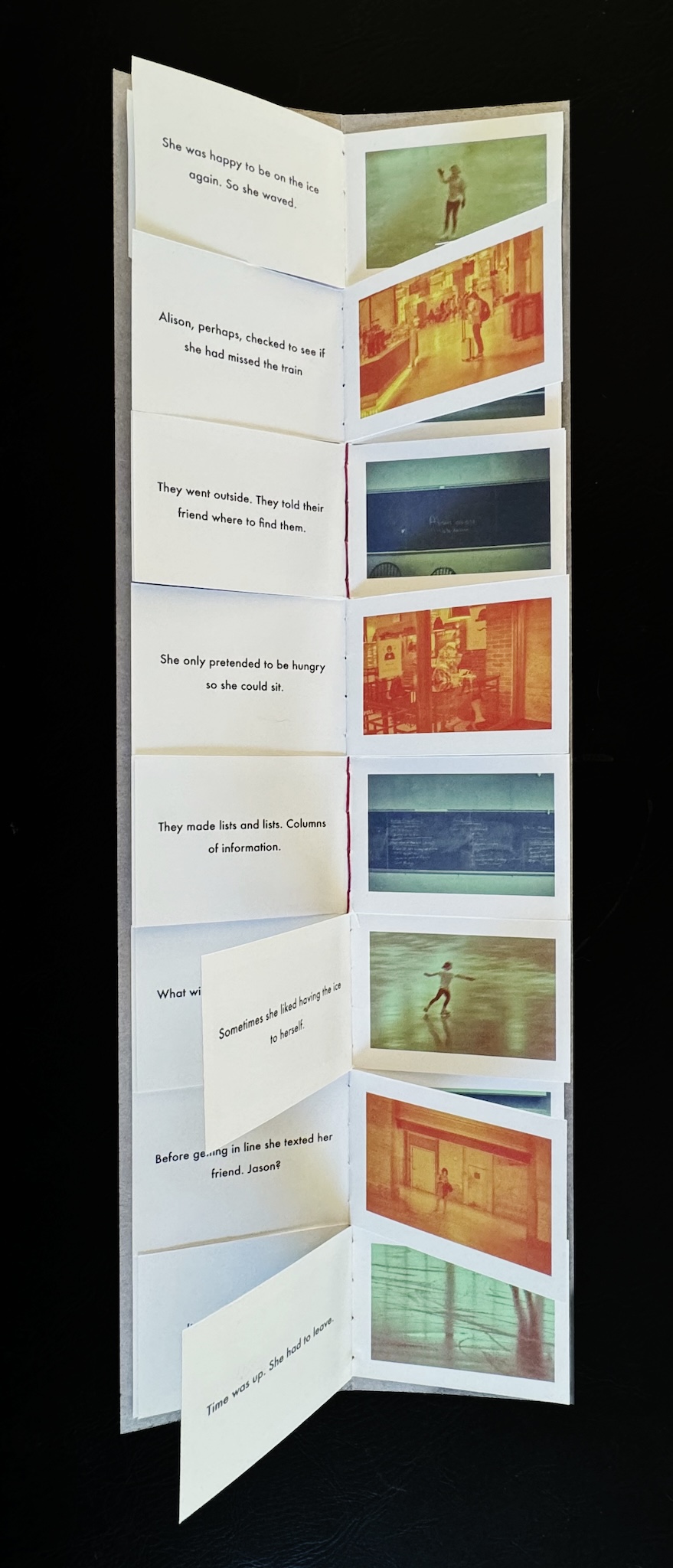

PBα

I often think of photographs in collections or series, linked to a single subject (e.g., an idea, place, time, experience). Given my preference for printed, physical photographs, I increasingly try to imagine a project in the form of an artist’s book. Artist’s books are not restricted by the format of a traditional book, sequential pages glued (or sewn) together. Instead, an artist’s book gives me the chance to play with form (accordion books, folding books, etc.). By taking advantage of these different forms, I can encourage people to imagine different ways to think about the relationship between photographs.

PBα #0. Recently I was playing with what I’ll call a “panel book” (“flap book” or “flag book” might be good terms as well, but let’s not dwell). In this initial experiment, three series of eight photograph-sentence pairs are arranged so that the reader can flip through each panel individually. The reader creates the series by flipping between photograph-sentence panels.

PBα #1. The book is an unusual shape, very narrow and tall at 2.75″x16″. The pages are stitched together inside a heavy stock cover. The paper I used for the pages was a bit thick (fortunately, I have since purchased some thinner paper). It took some planning to get the layout correct so that the printed pages would be in the correct order when folded and sewn. But now that I’ve figured it out, I’ll certainly be making more — I’ve already got PBβ planned.

PBα original #0.

PBα original #1. -

Style

But what’s a writer’s “style”?

Style is an expression of the interest you take in the making of every sentence.

It emerges, almost without intent, from your engagement with each sentence.

It’s the discoveries you make in the making of the prose itself.We assume that style is self-expression.

It can be, but only in this sense:

It’s the fusion of your command of language and your commitment to your own intent,

Even as your intent shifts under the weight and opportunity

Of the discoveries you make as you work,

Discoveries that are linguistic, conceptual, structural, imaginative.This doesn’t sound like a useful or conventional definition of style

V. Klinkenborg, Several Short Sentences about Writing, 84–85

Or much like self-expression.

But it does clarify an important thought:

“Style” shouldn’t linger in your awareness.

You don’t need to think about style. -

Melancholy

The days grow longer, already noticeable in the evenings. I will miss the dark mornings, early sunsets, and the long shadows cast by the pale winter sun. Light this time of year is magical.

Urban #231223.1 This woman sat in a small cone of warm light, shifting her gaze from the table in front of her to the darkening street outside. Now and then she lifted her cup to take a drink, absentmindedly setting it back down on the counter. She seemed content, at ease.

I love summer’s early sunrises and long days. But I will miss winter’s somber tones. Like many, I suffer from a sort of January melancholy, not because the days are short and dark but because they grow longer and brighter.