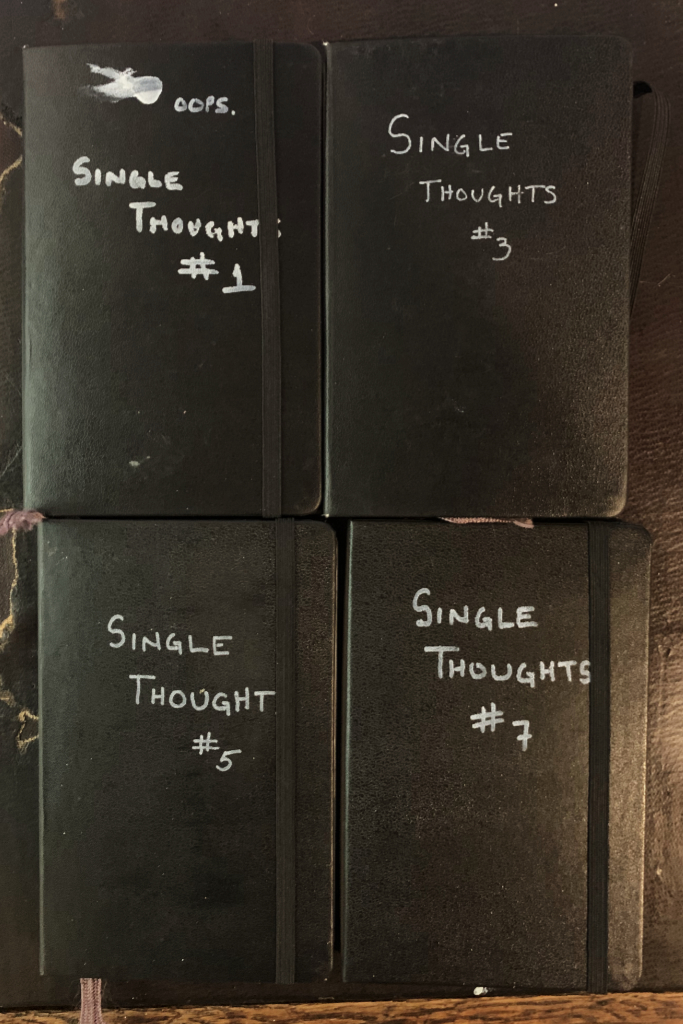

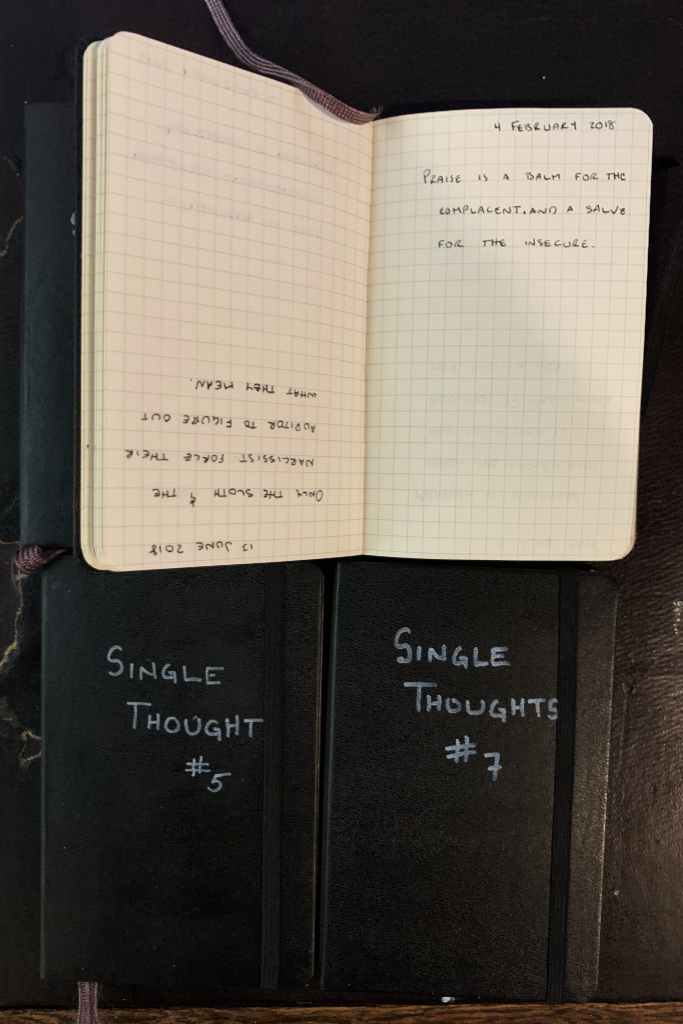

For a number of years now I have each morning written down a single thought. I had assumed a thought a day would be easy. It has been at times, however, surprisingly difficult. Some mornings I stare at the blank page and struggle to produce a thought, one that is my own. I take drink of coffee and in that moment the tendrils of thought reach up into my consciousness but retreat as soon as I set my coffee down and grab for my pen. Finally, I force out something that looks like a thought. Other days, thoughts trip over each other. But I need only one. Those mornings I merely filter out the bad thoughts and choose the one I like best.

Looking back over these thoughts, I have come to see that some are interesting, many are trite, and some incomplete. But the exercise is valuable for a number of reasons. First, sitting alone I know that nobody but I must see my thought. So if it is dull or boring or trite, that’s between me and the paper. The act of producing a thought, of writing it down, of seeing it on paper is valuable in itself. It keeps me from considering my thoughts precious or looking at them with some reverence. They are just something I write down each morning.

Second, the habit of writing a thought — good, bad, or neutral — each morning makes it easier to produce something. Now, after some time, I sit down with my coffee, pen in hand, open my notebook, and jot down a thought. I don’t tend to struggle as I once did. I doubt my thoughts have improved in consistent way, but by producing more of them I am able to produce more good ones.

Third, when I look back over these thoughts I begin to see patterns and trends. Some topics seem to recur, separated by a few dozen thoughts. Others erupt into my notebook, consume me for a week or so, and then fade. Often some seemingly random observations clearly agitate or animate me for a morning, never to return. There is no rhyme or reason to this series of thoughts, joined as they are by nothing more than chronology. But as fragments of my existence, they are interesting all the same.

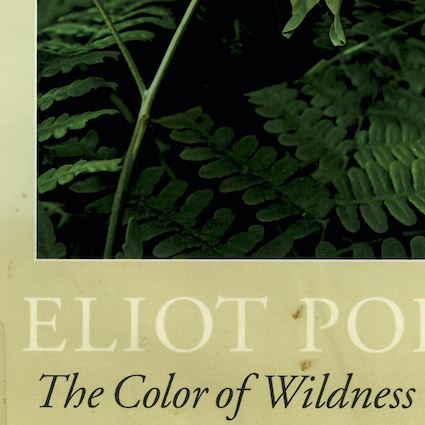

Finally, and perhaps most surprising to me, these thoughts encourage my photography. They offer thoughts or ideas that direct my attention, encourage me to look for something in the world, suggest a theme for a series of photographs. Sometimes they remind me that photography, like so many creative projects, needs to satisfy me. These thoughts also remind me that I can take photographs every day, photographs of whatever passes before me. It’s ok if many of those photos are trite, banal, or poorly executed. That’s between me and my camera. Some, however, will be interesting.