Autumn is here, bringing with it the drizzle of falling leaves and the carpet of those already fallen. Greens, yellows, reds, and browns, sometimes crowded together, sometimes by themselves. I wonder if they get lonely?

Autumn is here, bringing with it the drizzle of falling leaves and the carpet of those already fallen. Greens, yellows, reds, and browns, sometimes crowded together, sometimes by themselves. I wonder if they get lonely?

A personal trainer was cleaning up his equipment the other day in the park. He was wearing a shirt that said: “You don’t have to train today. The world needs average.” An odd combination of snarky and motivational. Nonetheless his shirt is a useful reminder that everyday is an opportunity to practice and through that practice to improve. So, to paraphrase:

You don’t have to take a picture today, but think of all the photos you’ll miss.

I really want to like this photograph, but something about it bothers me.

It has nothing to do with what’s in the frame and everything to do with what’s not in the picture. Or more precisely: What bothers me is what I had to do to get rid of something that was in the original picture.

I wandered around that corner for quite some time trying to get the right angle that would capture the window, the table, the building, and the sky. There was no ideal spot that isolated the building in just the way I wanted. So I settled for what seemed to be the best composition. Unfortunately, that composition had a massive building dominating the left half of the frame:

Easy enough to remove in post-processing. That’s why they invented the healing and inpainting brushes and the clone-stamp tool. A few minutes with my preferred editing program and the skyscraper was gone. Nobody would be any the wiser.

Except I know what I did. And for me, knowing that I cloned out half the frame ruins the final image. The effort to remove the offending building became an interesting exercise in how much manipulation I can accept. I have no problem with various local adjustments and will make small distractions disappear. But at some point it becomes too much for me. I don’t know where that dividing line falls, and I certainly can’t quantify it. But as a rule of thumb: When the manipulation changes the mood or tone of the photo entirely, as it does in the images here, it is too much for me.

Two caveats: First, my rule of thumb is almost certainly grounded in some combination of a romantic notion of photographic integrity and a preference for one type of labor (walking around and looking for the perfect frame) over another (editing on a computer). Second, this is my rule of thumb for my photographs, and is not meant to apply to anybody else or that person’s photographs.

I was wandering the city that overcast Wednesday afternoon. While not empty, as it had been in the early months of the pandemic, it was not bustling in any normal way. Most offices in the city remained closed or only sparsely staffed. So I took the chance to look for scenes that would capture the emptiness. Glancing up at one corner, I noticed a table next to a window in a low-rise office building.

Nine months ago, I probably could have waited long enough to catch somebody standing at the window, transforming this photo from a minimalist picture into an Edward Hopper-esque photograph.

Even without the person, I really like this photo. It captures the image I had hoped to find that afternoon. I like the loneliness it suggests. The table that earlier this year would have been a meeting place for colleagues to chat and share some gossip, or a place for somebody to take a quick break is today collecting dust, like so many tables and desks in offices everywhere.

Knausgaard’s collection of essays is a joy to read. While the essays in Autumn are all quite good, the real pleasure comes from the physicality of the book. The coarse texture to the dusk jacket.

The pages are a smooth, heavy paper that has a sensuous feel. The illustrations and the printed words look better on this paper, in part because the pages are pleasure to hold and to turn.

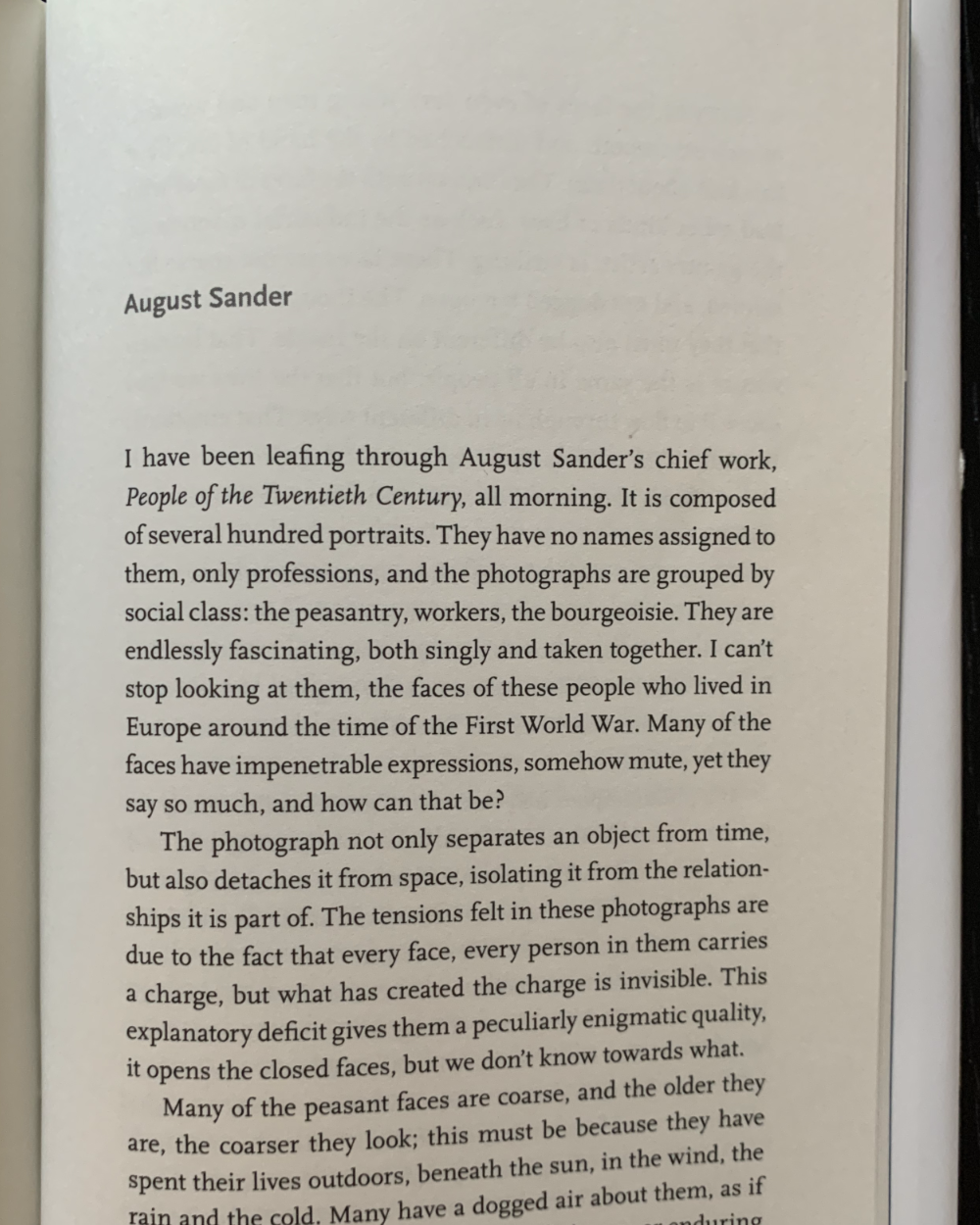

Knausgaard has a smart essay on August Sander that hints at the value of printing your work in book form, and the challenge and allure of photography. About Sander’s work, he says (in part):

… They have no names assigned to them, only professions, and the photographs are grouped by social class: the peasantry, workers, the bourgeoisie. They are endlessly fascinating, both singly and taken together. I can’t stop looking at them, the faces of these people who lived in Europe around the time of the First World War. Many of the faces have impenetrable expressions, somehow mute, and yet they say so much, and how can that be?

The photograph not only separates an object from time, but also detaches it from space, isolating it from the relationships it is part of. The tensions felt in these photographs are due to the fact that every face, every person in them carries a charge, but what has created the charge is invisible. This explanatory deficit gives them a peculiarly enigmatic quality, it opens the closed faces, but we don’t know towards what.

These essays, like Sander’s photographs, are endlessly fascinating singly and taken together. They offer a tactile experience that enriches the reading. Their sequence in the book reflect an intentionality and invites us to think about how that order reveals something more than the individual essays can. They encourage us to move slowly through them, perhaps leafing back now and then to make connections to resolve or identify tensions between them.

Similarly, I think, physical photographs encourage us to slow down, to pause, to lay them out next to each other and compare them. If they are printed in a book, the arrangement and grouping tell us more than the individual photographs could. In either case, individual prints or sequences in books, there is a sensual pleasure in holding a photograph that has been printed on good paper.

Photography seems always to imagine a different world. Photographers don’t record the reality they see, they consecrate a reality they wish to see. In this way, photographs are always about a world that no longer exists. The lure of dilapidated buildings, of abandoned places, and of weed-choked roads testify to the photographer’s urge to record and celebrate lost scenes. Photography teeters between preservation and nostalgia.

It is difficult to preserve without the taint of nostalgia, as is the case now as I look over some photographs taken before the Bobcat Fire devastated so much of the San Gabriel mountains and Santa Anita Canyon. Loss and destruction had always lurked along the trail up Santa Anita Canyon in the remnants of previous structures scattered through the trees.

But now the various photographs intended, for the most part, to preserve what I saw as I hiked up the canyon have become a poignant reminder of how much more we have already lost. These photos are also a warning for what will likely be lost when the mud and debris slides down into the canyon and chokes the creek.

Along with the mud and debris will come the dead trees. Many will fall, blocking the trail and clogging the creek. Others will never leaf out again. Their canopy of leaves that shades the trail through the canyon has certainly been lost.

And then there are the camps, Spruce Grove Campground and Sturtevant Camp. Whether or not they have been destroyed, they are closed for the foreseeable future, as is the trail leading to them.

Now, in light of the recent fires, these photographs do more than just preserve moments. They evoke a powerful nostalgia, reminding me not only of the hike that produced these images but also all the hikes over the years as friends and I squandered our youth in these mountains.

Friday evening around 8:00pm. Tired professionals should have been driving home or to meet friends at a local restaurant or bar. But instead the street was empty. I stood there in the middle of Lancaster through two cycles of green-yellow-red, green-yellow-red. On one side a Chevy van sat empty with its flashers blinking. On the other side, a Toyota Prius jutted out from between two buildings, its flashers silently signaling to the van’s. Perhaps they were meant to pick up food for those professionals who haven’t been into the office for weeks.

The sidewalks are empty, as are the restaurants and bars. Yet all the restaurants and bars are lit up as if waiting for customers to return. I feel like I’m in an episode of The Twilight Zone in which all the people have suddenly vanished, leaving me to wander the streets alone.

Welcome to the new normal in Ardmore.

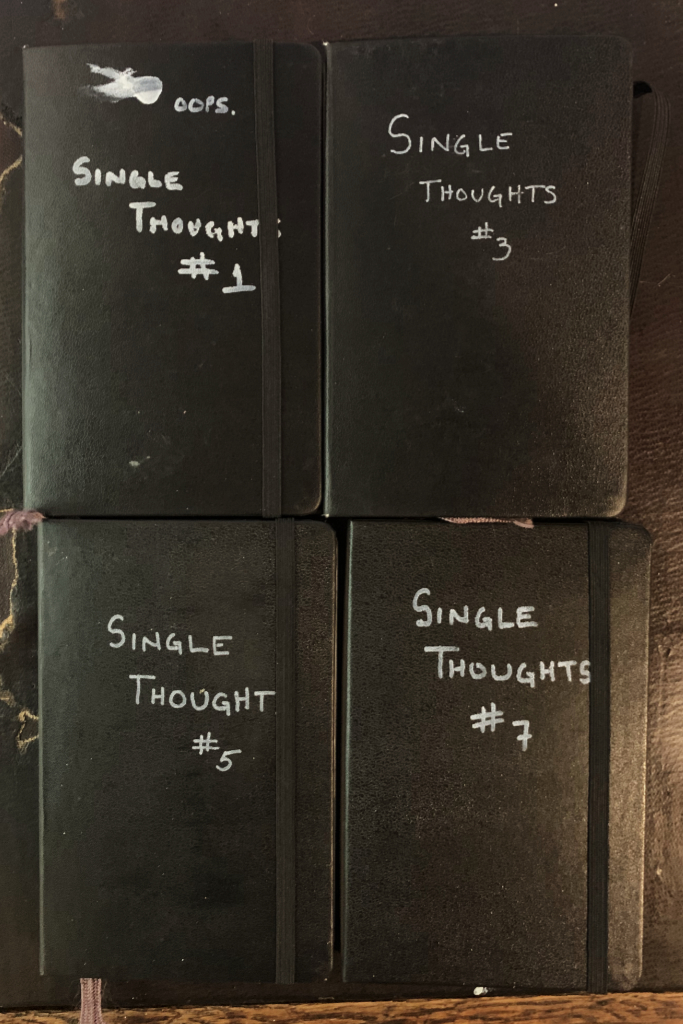

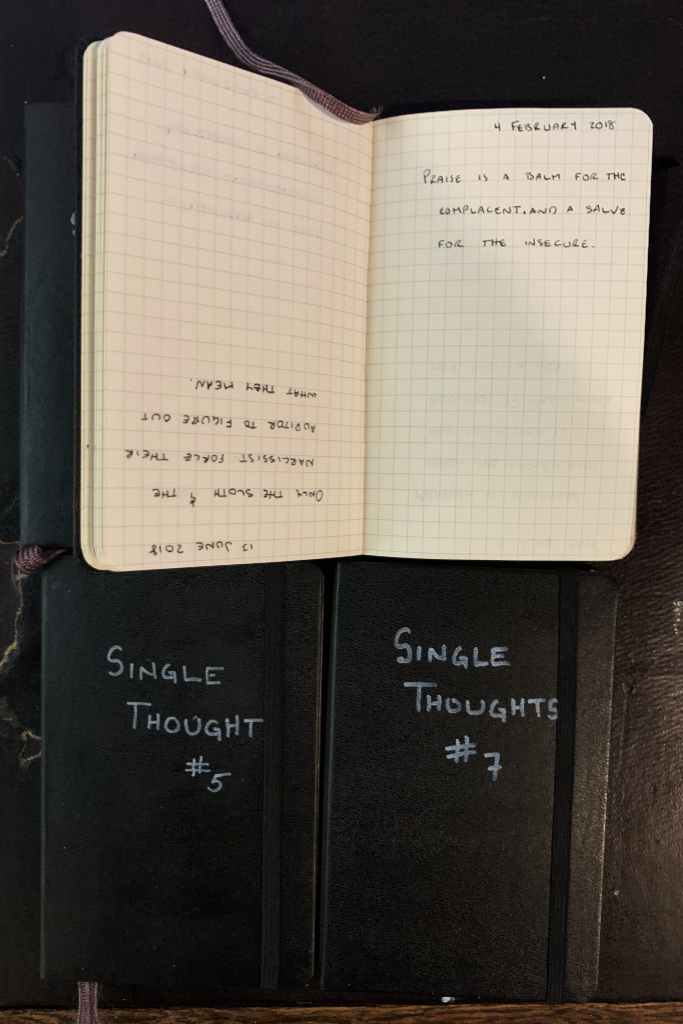

For a number of years now I have each morning written down a single thought. I had assumed a thought a day would be easy. It has been at times, however, surprisingly difficult. Some mornings I stare at the blank page and struggle to produce a thought, one that is my own. I take drink of coffee and in that moment the tendrils of thought reach up into my consciousness but retreat as soon as I set my coffee down and grab for my pen. Finally, I force out something that looks like a thought. Other days, thoughts trip over each other. But I need only one. Those mornings I merely filter out the bad thoughts and choose the one I like best.

Looking back over these thoughts, I have come to see that some are interesting, many are trite, and some incomplete. But the exercise is valuable for a number of reasons. First, sitting alone I know that nobody but I must see my thought. So if it is dull or boring or trite, that’s between me and the paper. The act of producing a thought, of writing it down, of seeing it on paper is valuable in itself. It keeps me from considering my thoughts precious or looking at them with some reverence. They are just something I write down each morning.

Second, the habit of writing a thought — good, bad, or neutral — each morning makes it easier to produce something. Now, after some time, I sit down with my coffee, pen in hand, open my notebook, and jot down a thought. I don’t tend to struggle as I once did. I doubt my thoughts have improved in consistent way, but by producing more of them I am able to produce more good ones.

Third, when I look back over these thoughts I begin to see patterns and trends. Some topics seem to recur, separated by a few dozen thoughts. Others erupt into my notebook, consume me for a week or so, and then fade. Often some seemingly random observations clearly agitate or animate me for a morning, never to return. There is no rhyme or reason to this series of thoughts, joined as they are by nothing more than chronology. But as fragments of my existence, they are interesting all the same.

Finally, and perhaps most surprising to me, these thoughts encourage my photography. They offer thoughts or ideas that direct my attention, encourage me to look for something in the world, suggest a theme for a series of photographs. Sometimes they remind me that photography, like so many creative projects, needs to satisfy me. These thoughts also remind me that I can take photographs every day, photographs of whatever passes before me. It’s ok if many of those photos are trite, banal, or poorly executed. That’s between me and my camera. Some, however, will be interesting.