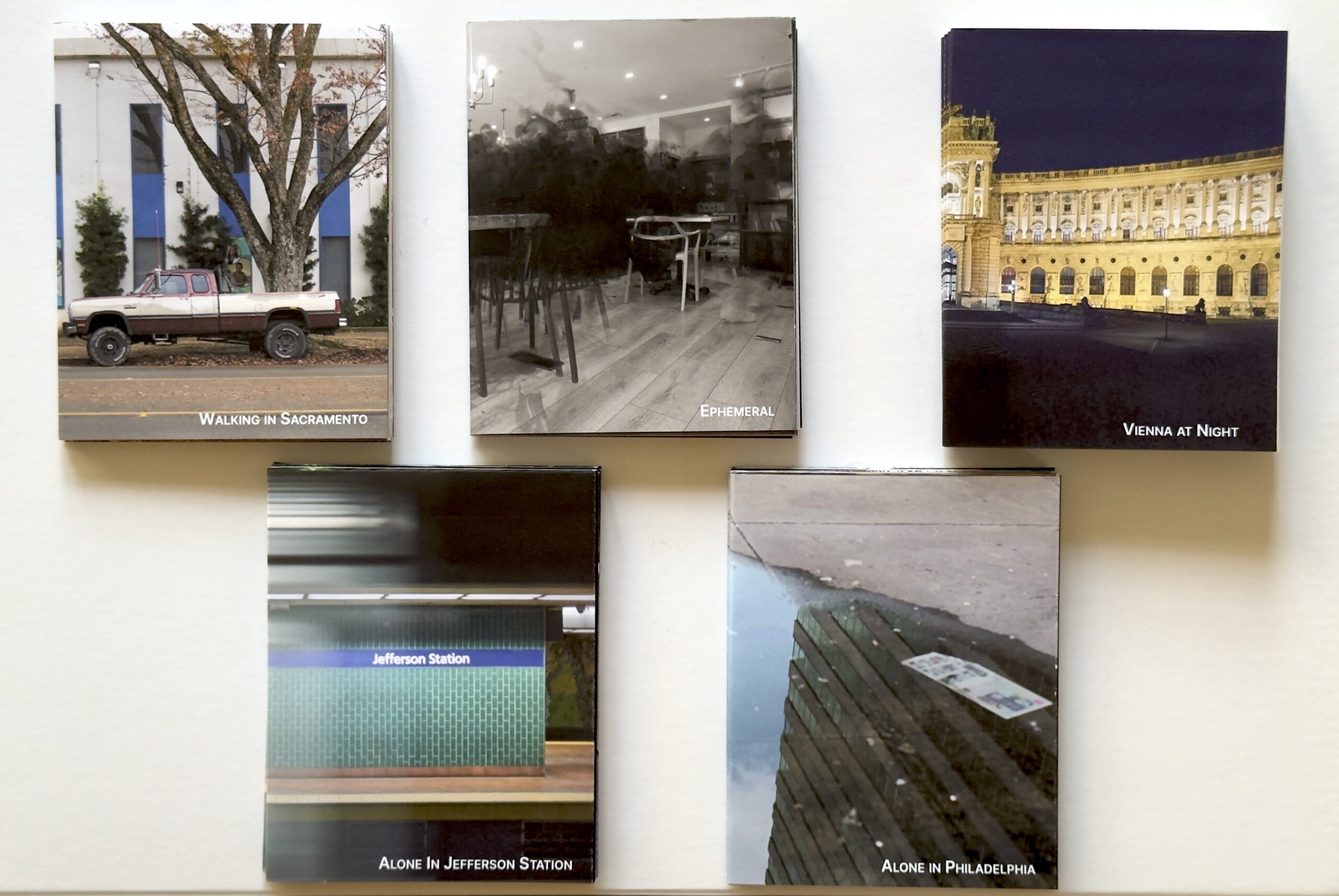

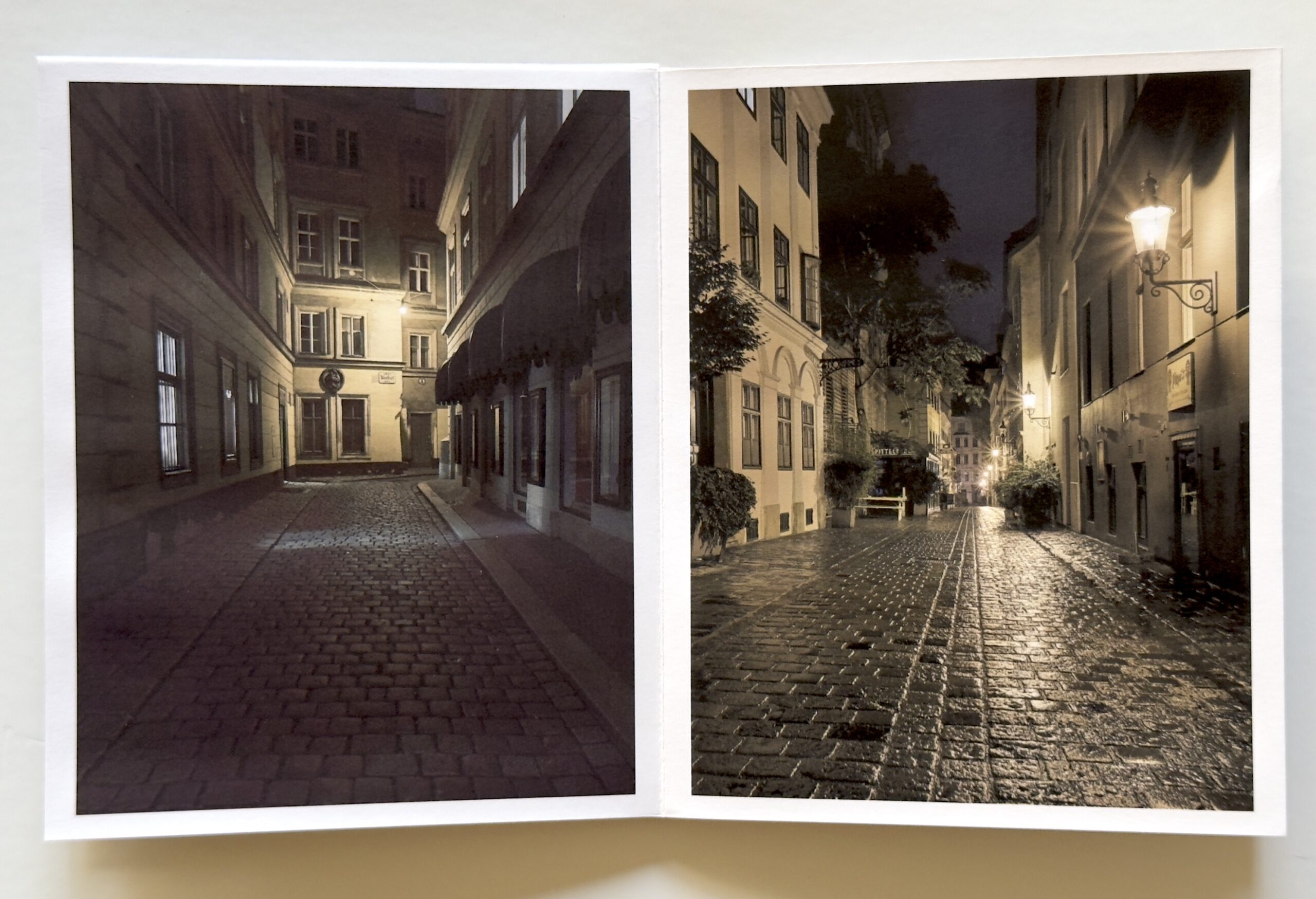

I like making things. Little things. Big things. Lately, I’ve been having fun with an 8-page zine. Printed from one piece of paper, folded, and cut, it is to me the ideal format for a short outing, or for a case study of a place. Or, I can look back through photographs I’ve taken to find a group of 8 that make a good theme.

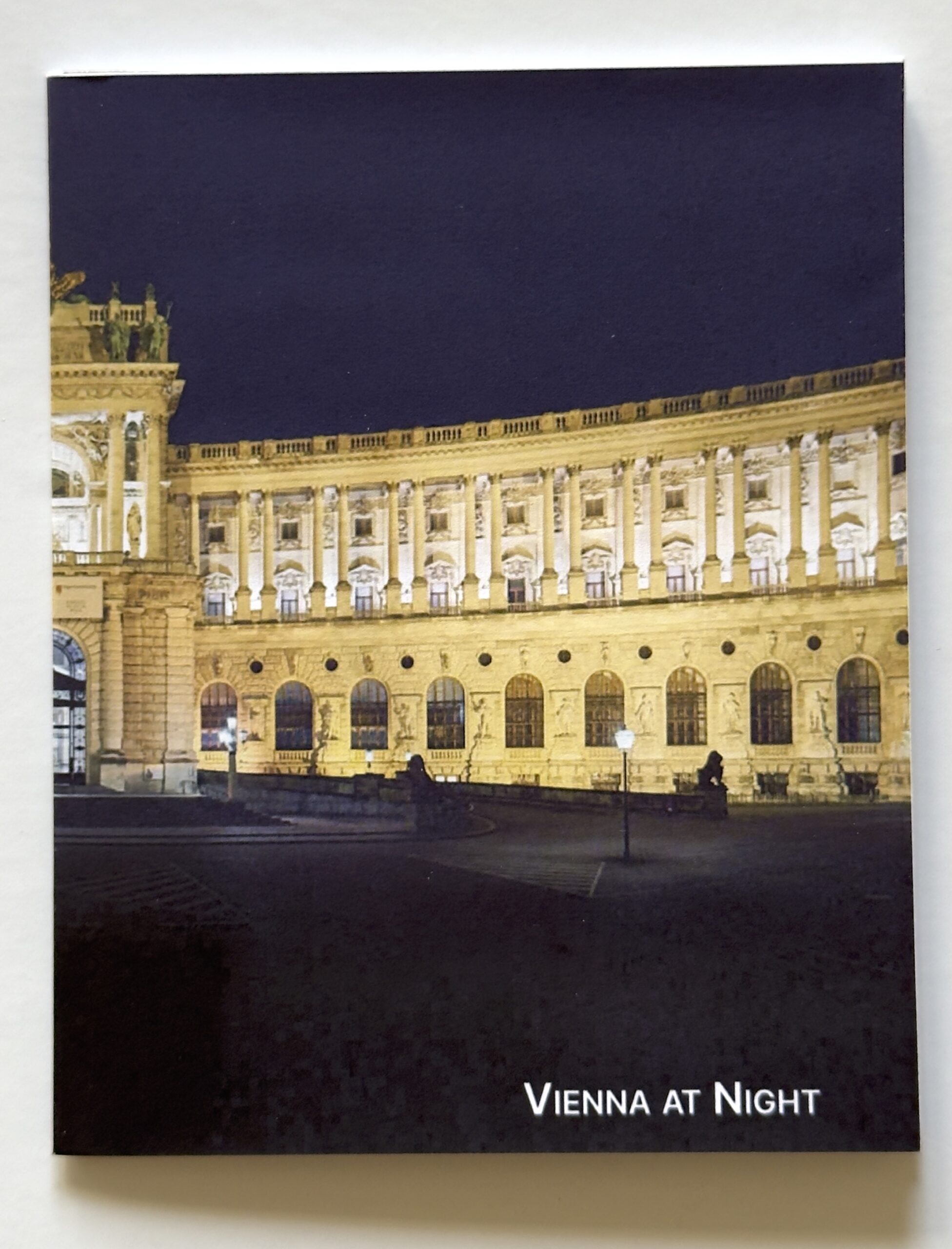

They are easy and relatively quick to print and to fold. I use 11″x17″ sheets of paper, so that each page is about 4″x5″, large enough to showcase the photographs but not so large as to be bulky. I tweaked the layout a bit so that the cover image wraps around the front and back covers.

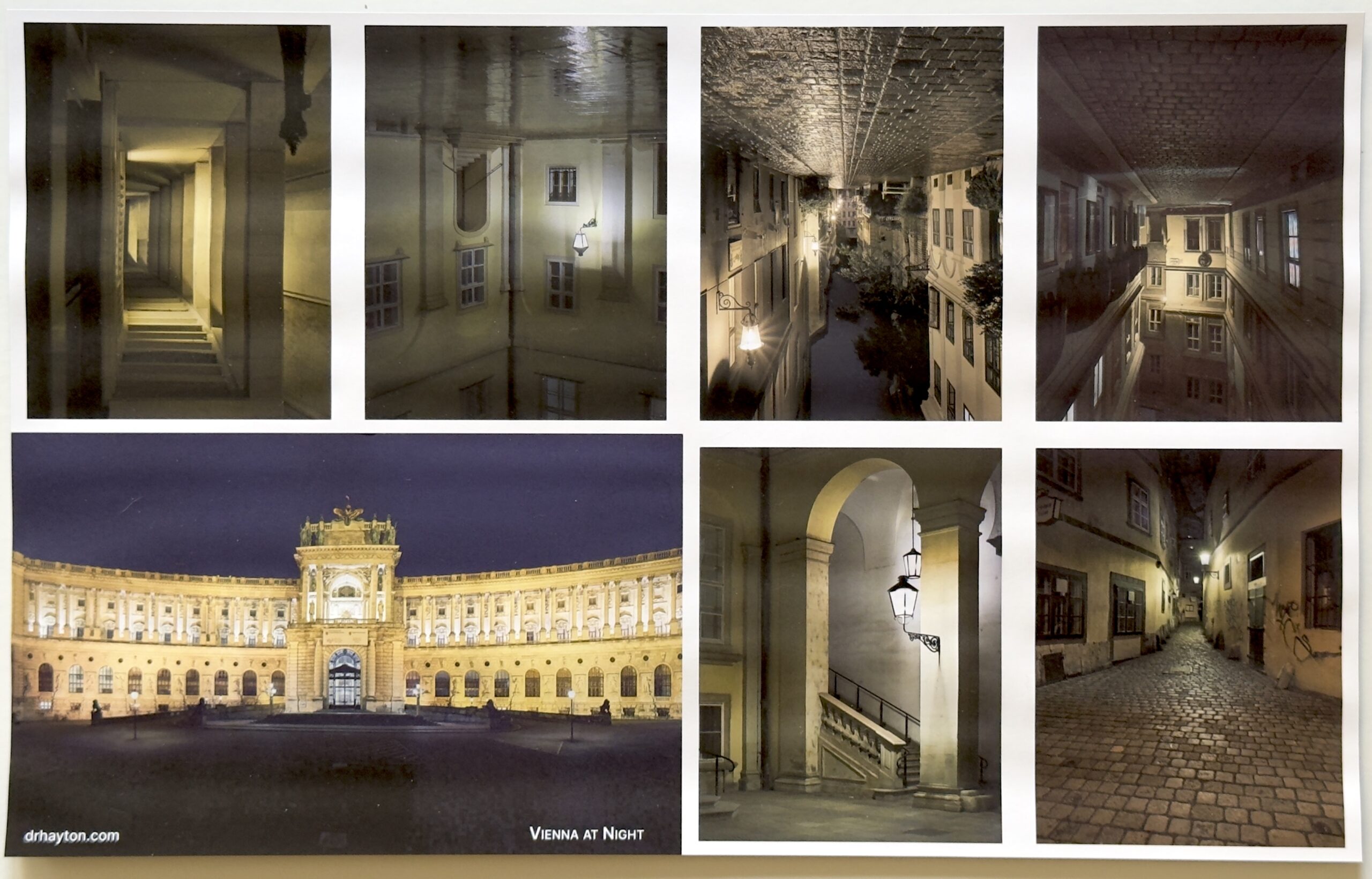

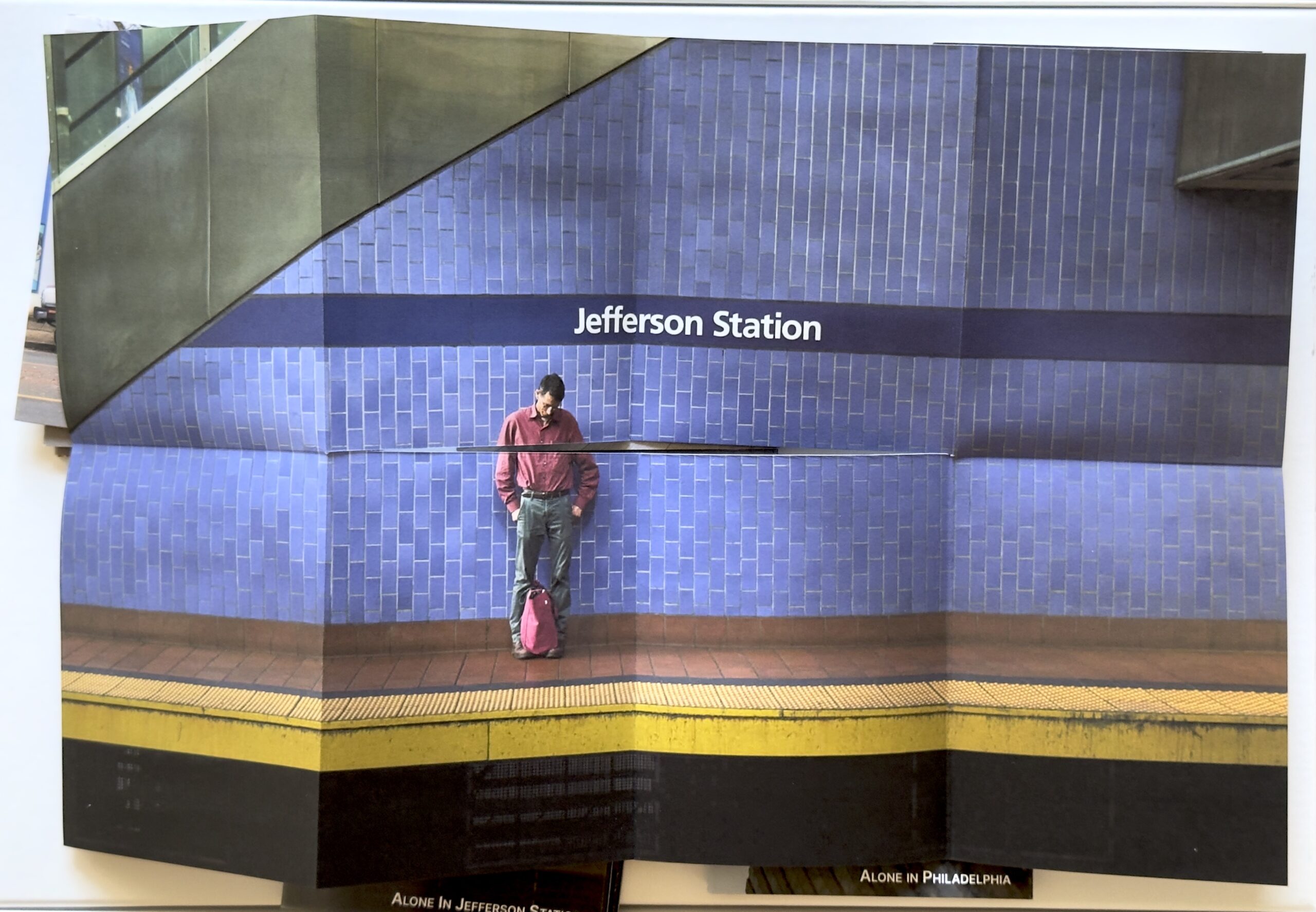

This format also gives a place to print a large photograph on the back side. It’s sort of a surprise for the person looking at the zine, and a puzzle — it seems unfolding and refolding the zine presents something of a challenge for people, which I didn’t expect.

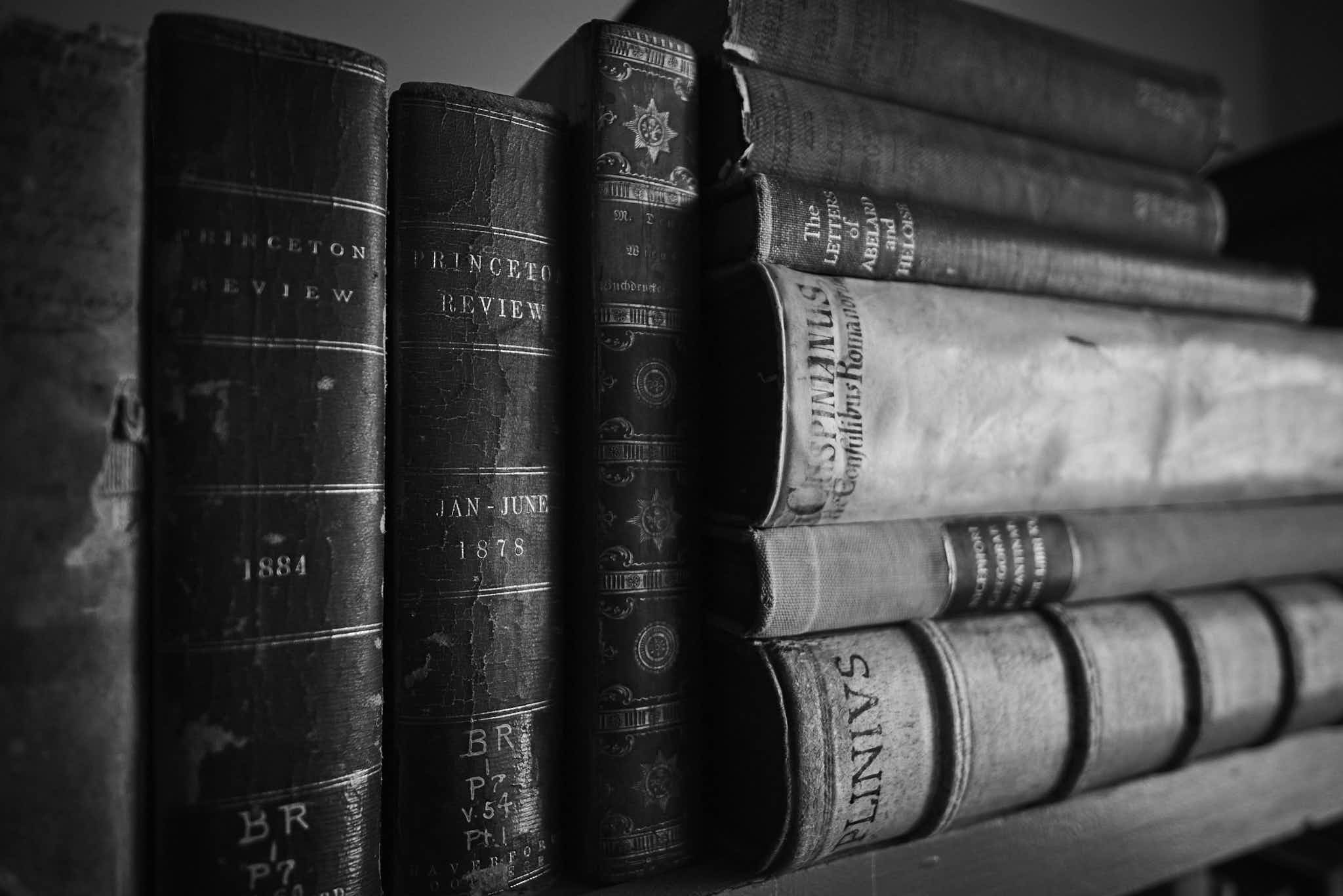

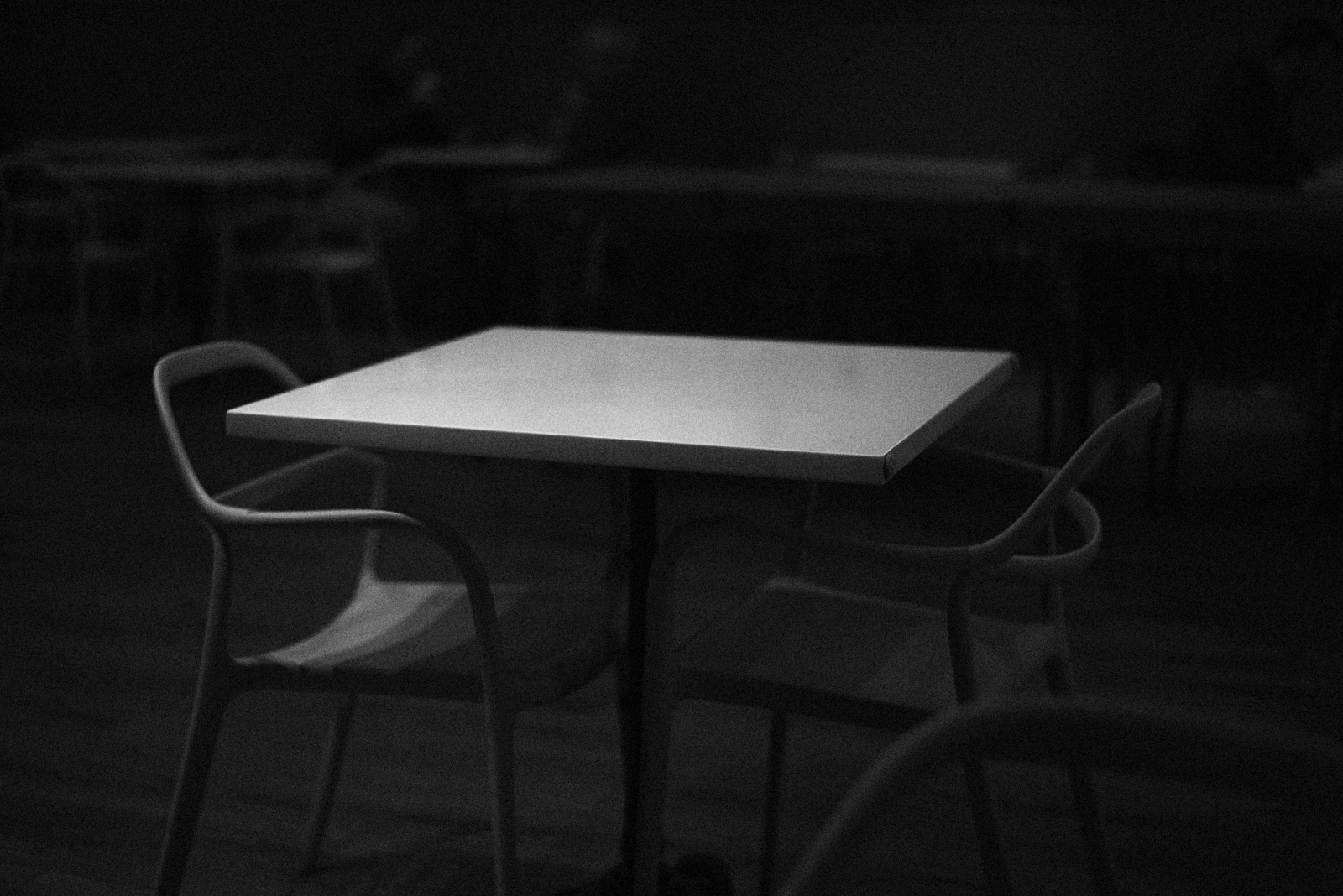

When it is all done, trimmed, folded, and cut, the zine is the perfect size for my guerrilla art projects. I have given them to friends and handed them to people I don’t know, left them on tables and shelves in coffeeshops, stuffed them between books in libraries and bookstores, and left them on seats in buses.

I don’t know what happens to those I abandon in the world. And I don’t really care. The point, for me, is in the making and giving away (not, I stress, “sharing” which has become an essential part of the economy of likes, has become entirely transactional, and depends on knowing what happens to whatever you make).

Sometimes I leave the house, camera in hand, looking for a coherent set of images that work well together. That was the case with the “Walking in Sacramento” or the “Alone in Philadelphia” zines — I knew an afternoon’s walk would produce at least 8 scenes I could cobble together into a zine. Other times, I draw from a few trips out and about, as in the “Vienna at Night” zines (there are two of these zines, gathering together the photographs from a few nights wandering the city late at night). In other cases, a zine emerges when I’m looking back through photos I’ve taken over a number of trips out. “Alone in Jefferson” is that type — the central image is part of a collection of photographs I’ve taken usually in Jefferson Station that highlight the loneliness of the modern world.

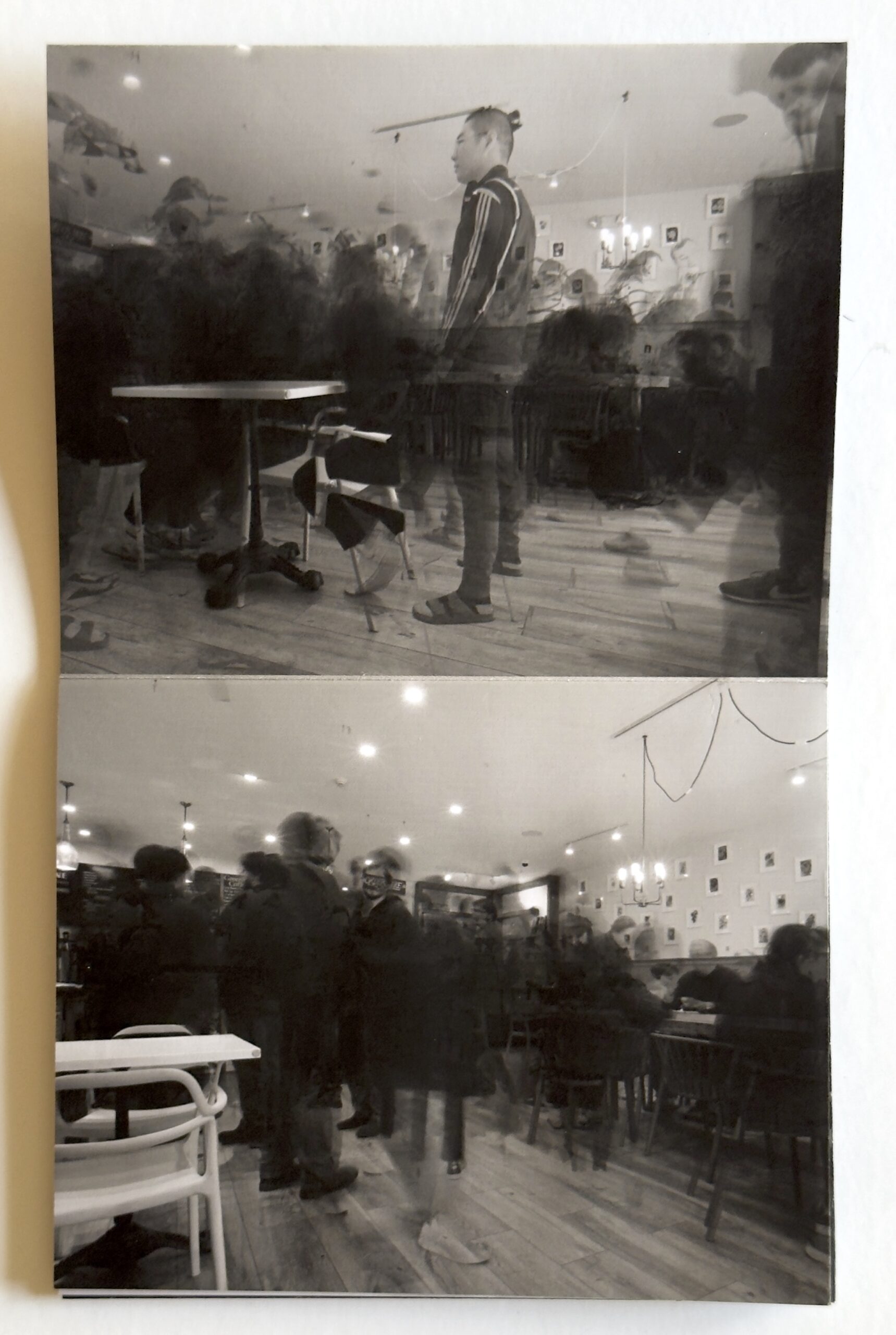

Any group of 8 photographs that cohere can become one of these little zines. Inspired by Alexey Titarenko, I took a bunch of photographs of people in a local cafe (see Ghosts in the Cafe). Turns out I have 8 that work well together, so I printed them as a zine. Seems appropriate that I left a handful in that cafe.

Like all of my projects, this one will last as long as I find it amusing or interesting. I will continue to print copies of these zines, and cast them into the world. If you’d like to receive a few, send me $10 and your address. I will send you three random zines. Or, offer something in exchange.