The vagueness of a daily photography project or the magnitude of a “365 project” has always put me off. A more finite, one still life each day for a month, worked better. Even that project, however, lost some of its appeal by the end:

However, I have largely disliked this project. I find it dull. I have fallen into the habit of thinking that making the single photograph (which I do each evening) is sufficient. As long as I do that, I’ve accomplished something for the day. Consequently, I find myself taking fewer photographs as I wander with my camera. As if I’ve replaced taking photos of the world around me with taking my daily flash photo.

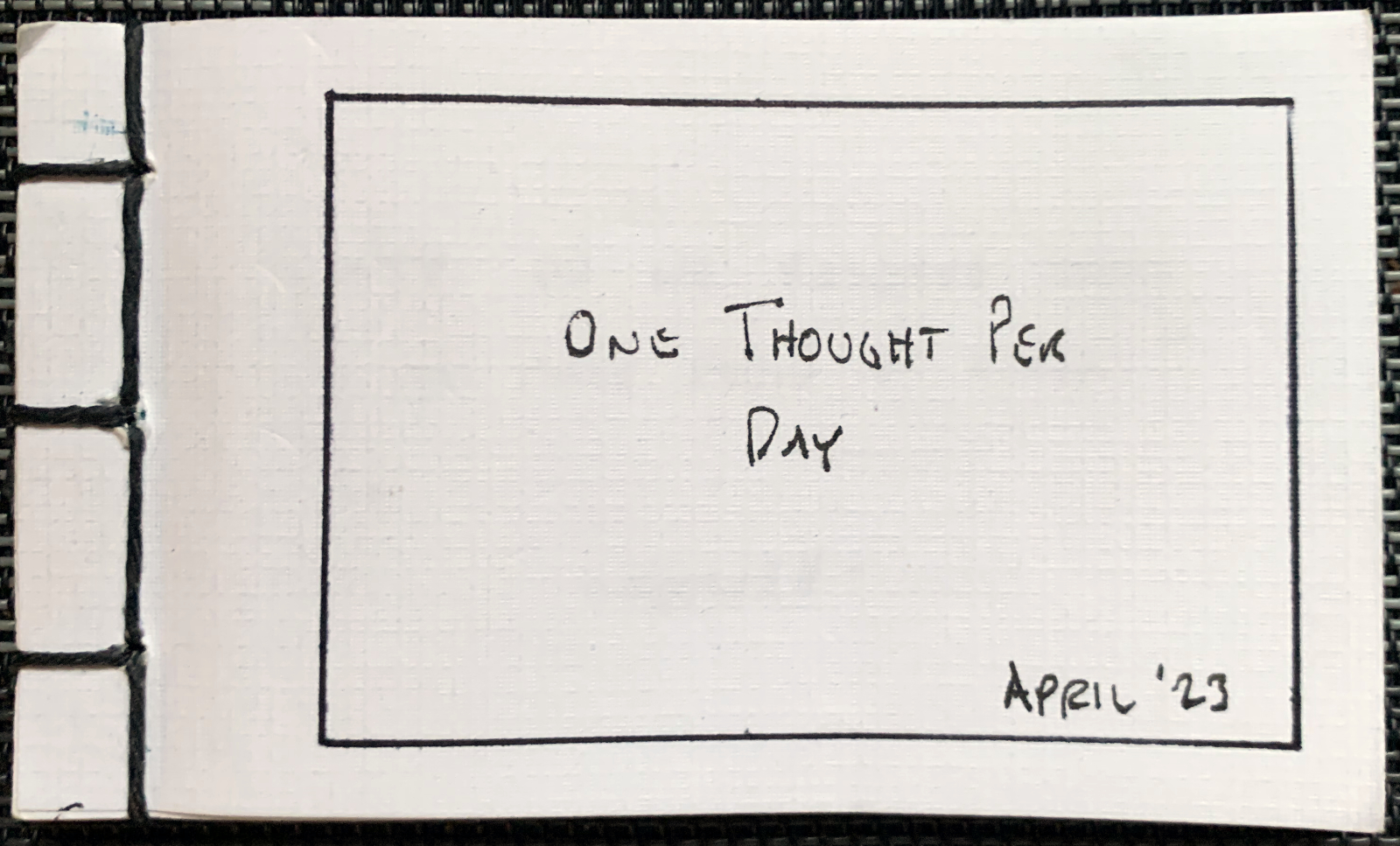

The monotony was both too boring and not sufficiently compelling. As I said at the end of that project, maybe something more focused — my version of Micheal Beirut drawing his left hand every day, or Joseph Sudek photographing things in his window. An important aspect of such a daily project, for me, is prompting me to look at the world in new ways. Trying to capture that aspect, I have been working on a daily project this past month: “One Thought Per Day.”

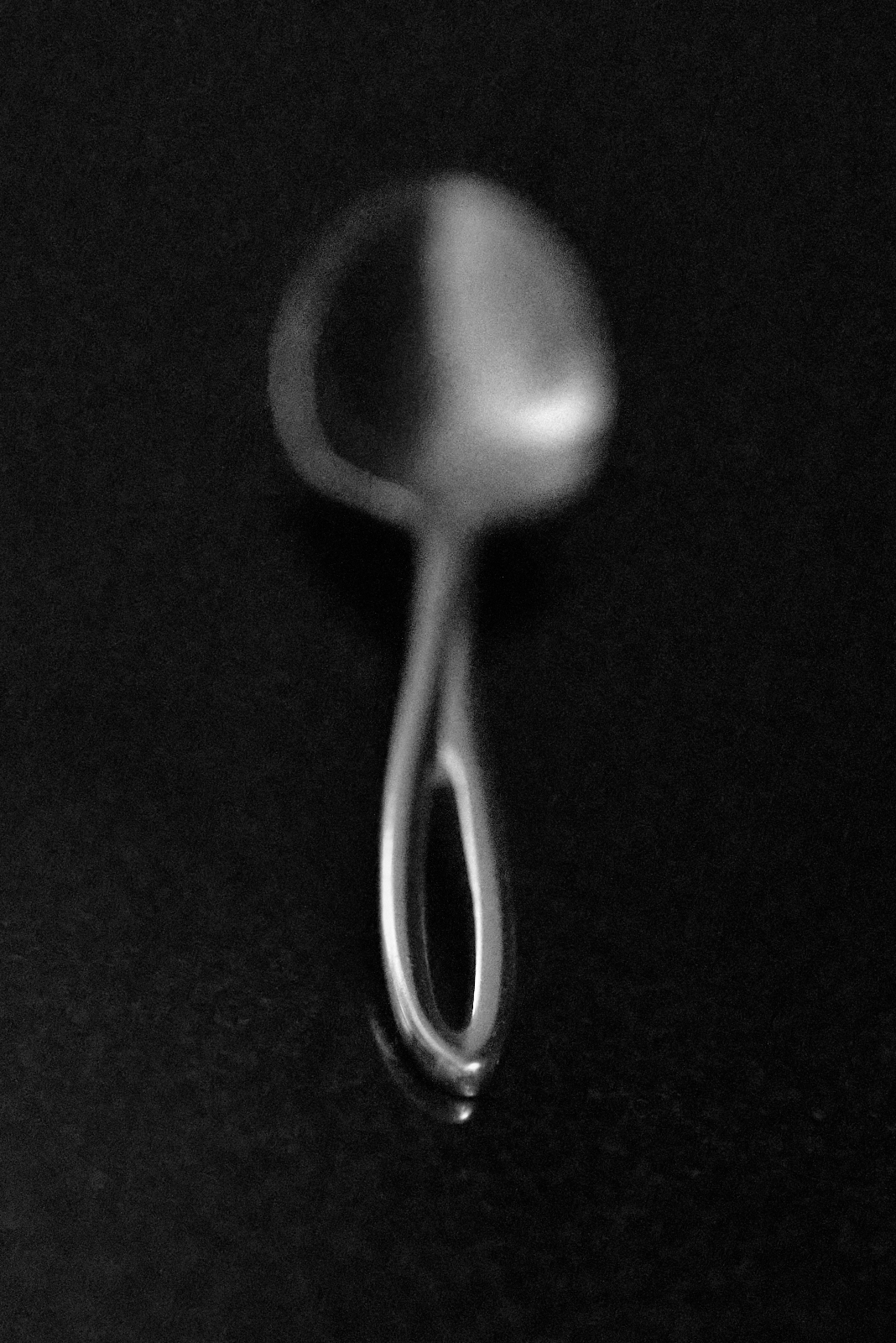

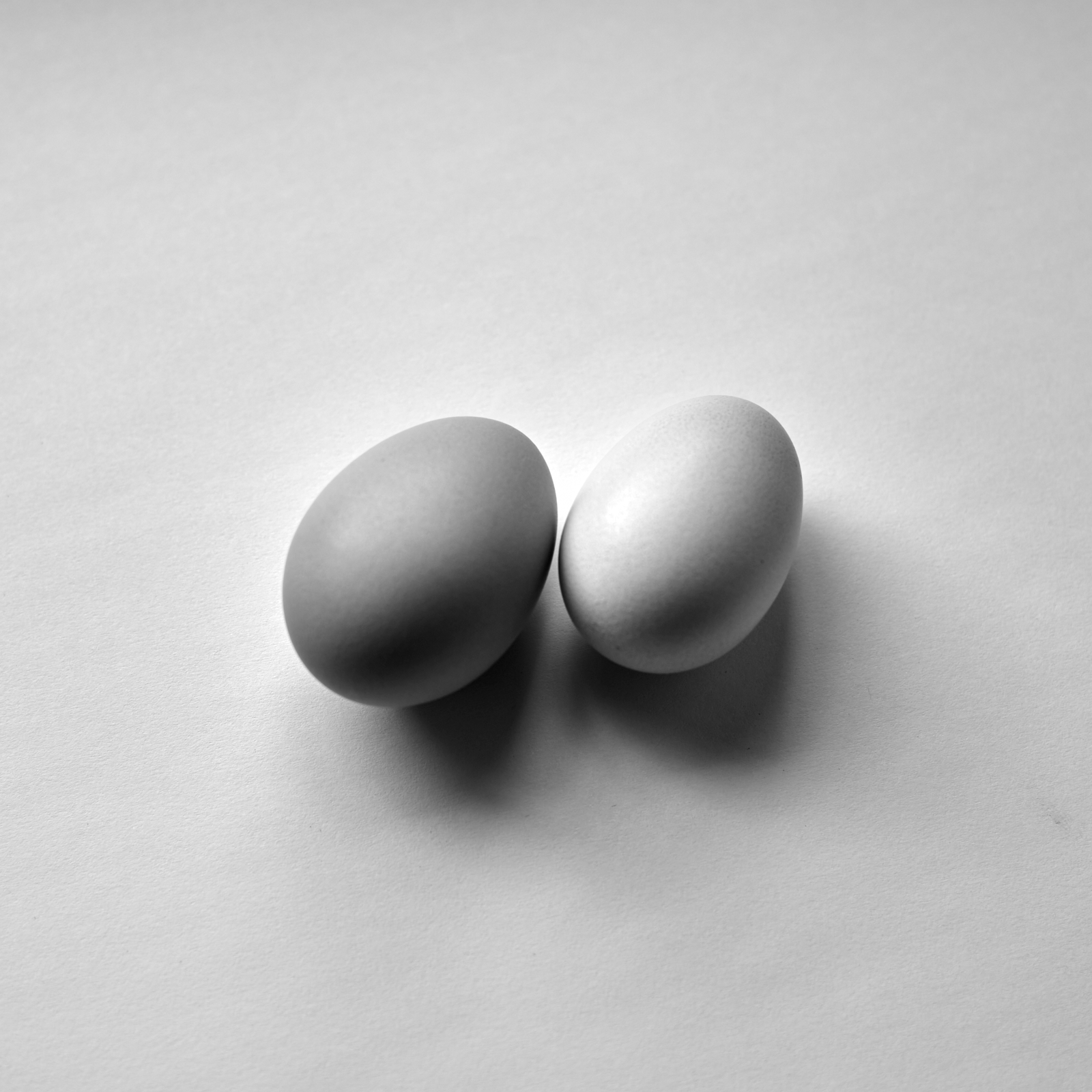

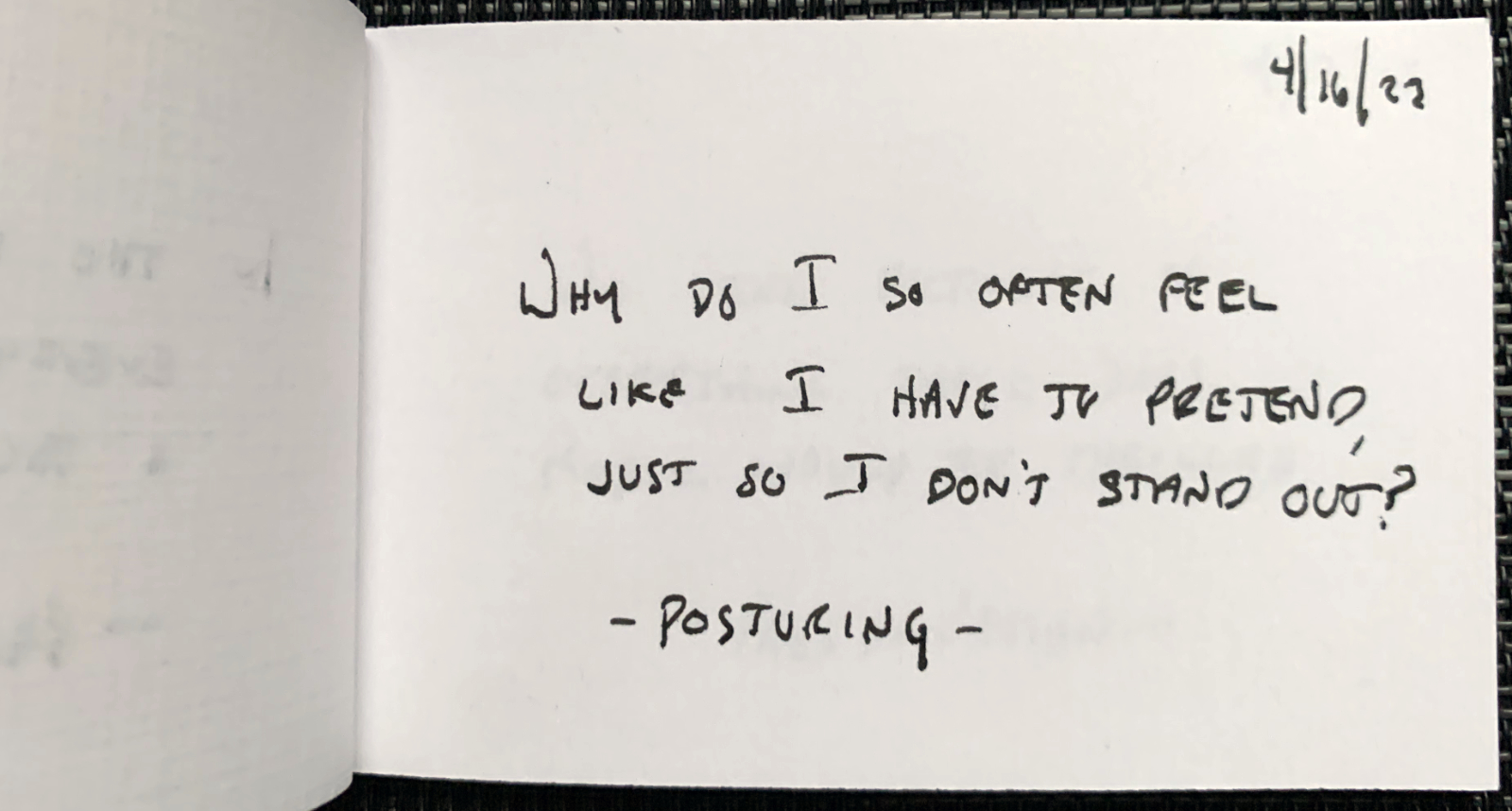

I made a little booklet, a sort of diary. Early each day I write a thought, sometimes a question, on the day’s page. From that thought I generate a single word. That word guides me as I look for a scene (I don’t get to stage it — I must find it) that relates to the day’s word/thought. I get to take one picture.

The page above shows the thought for April 16, 2023. Posturing, pretending to be something I am not, was the thought that I sought to find as I went through the day. I found, standing on a windowsill in the department lounge, a small articulated mannequin (why an IKEA mannequin is in the lounge I can’t imagine). It became the day’s photograph.

At the end of the month I will print the day’s on a page the precedes the day’s photograph, and then assemble them into a booklet (the same dimensions as the diary I use to record the thoughts). In the end, I’ll produce a small booklet, 2 1/2″ x 4 1/4″, of about 60 pages — 30 thoughts and 30 photographs, which I will hand bind.

For me, the combination of thinking, writing, searching, and photographing has been really productive. Guided by an idea or thought, I have looked at the world around me for scenes that somehow capture that thought. I have found that I spend more time thinking about the world as I move through it. I don’t know if I have taken more pictures because of it, but I think that I’ve put more thought into most of those pictures.

I also just love making things, material things. I enjoyed making the little booklet in which to record my thoughts. I am looking forward to making the booklet filled with those thoughts and the photographs they generated.

As with most of my projects, I will likely make a handful and leave them places, cafes, Little Free Libraries, benches, wherever. I’ll probably send some to random people as well. For me, that is an important part of my entire project. Casting whatever I make out into the world (Nick Tauro Jr.’s version of this is brilliant — if only I had an old newspaper box).